Dear Editor,

A 9-month-old male infant, with appropriate neuropsychomotor development, presented withan approximately two-week history of fever and seizures. The prenatal monitoring anddelivery had been unremarkable. Serological tests for cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis,and HIV were negative, as was the venereal disease research laboratory test. Thecomplete blood count, electrolyte analysis, and analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid allshowed values within the normal ranges, with only a slight increase in erythrocytesedimentation rate. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed an extra-axialexpansile lesion exerting a compressive effect on the right frontal lobe, presentinghypointense signals in T1-weighted and T2-weighted sequences, together with markedgadolinium enhancement in T1-weighted sequence (Figure1). Histopathological and immunohistochemical studies revealed granulomatousmaterial with monoclonal Langerhans cells, Birbeck granules, and CD1a positivity,confirming the diagnosis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH).

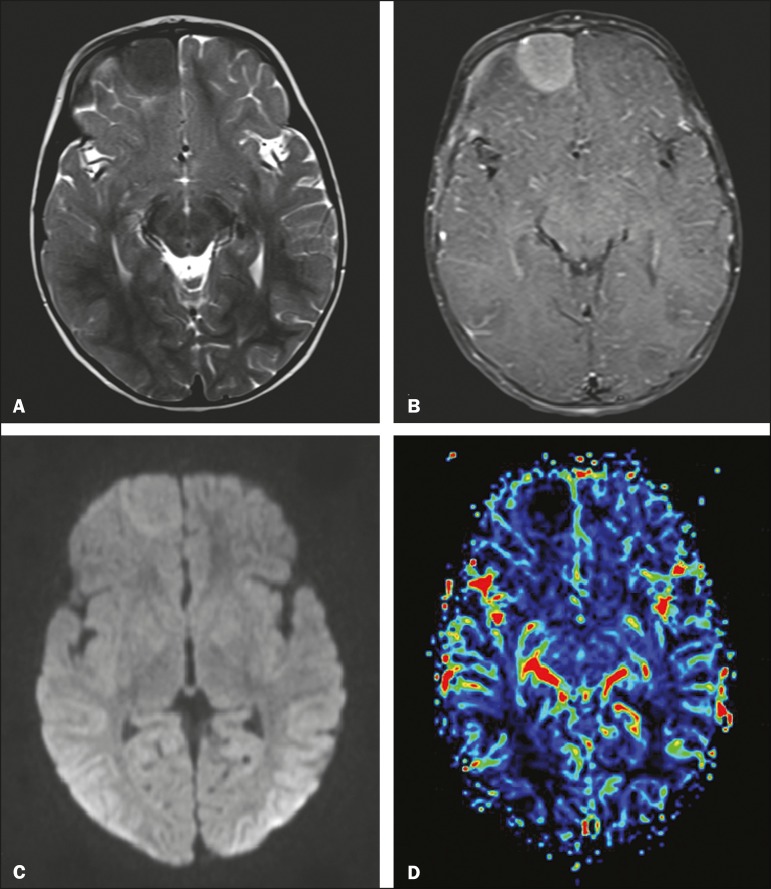

Figure 1.

MRI. A: Axial T2-weighted image showing an extra-axial expansile lesion inthe right frontal region, with precise, homogeneous and hypointense limits.B: Contrast-enhanced axial T1-weighted image showing marked gadoliniumenhancement. C: Axial diffusion-weighted sequence showing a signal that isisointense in relation to that of the brain parenchyma. D: Map of therelative cerebral blood volume, demonstrating the absence of signs ofhyperperfusion.

LCH is a rare systemic disease of unknown cause, presenting a variable clinical course,from spontaneous regression and chronic recurrence to rapidly progressive deteriorationwith evolution to death(1-4). It can occur at any age but is mostcommon in children, primarily in those between 1 and 4 years of age, with an incidenceof 1 case per 200,000 children(3,4). Histopathological andimmunohistochemical analysis reveals granulomatous infiltrates composed of monoclonalLangerhans cells, T cells, and eosinophils, with Birbeck granules and CD1apositivity(1,5).

The main organs affected by LCH, in descending order of frequency, are the bones (in80%), skin (in 33%), pituitary gland (in 25%), liver (in 15%), spleen (in 15%), and lung(in 5-10%); involvement of the pituitary gland typically manifests as diabetesinsipidus(5). In approximately2-4% of the cases, there is involvement of the meninges, choroid plexus, pineal gland,and cerebral parenchyma, potentially provoking symptoms related to a compressive effector cerebellopontine dysfunction, as well as neurodegenerative symptoms(1,2,4,5).

Extra-axial involvement is more common in LCH because of the extent of the bone lesionsaffecting the skull, and the exclusive involvement of the meninges is rare, asdemonstrated in this case(1,2). MRI shows an expansile lesion, with abroad dural base, that is homogeneous, with a hypointense signal in T1-weightedsequences and an intermediate to hypointense signal in T2-weighted sequences, withmoderate to marked gadolinium enhancement(1,2,4).

There have been few reports of the behavior of histiocytosis in advanced MRI sequences.In our case, the lesion presented low signal intensity in a diffusion-weighted sequence,which is in accordance with the findings of Miyake et al.(6), possibly secondary to the low cell content of thelesion. Classically, histiocytosis lesions do not show signs of hyperperfusion, becausethey are essentially lymphoproliferative disorders without neoangiogenesis. However,Hingwalaa et al.(7) reported a case inwhich there was increased perfusion, with high positivity for CD34 and CD31, which areintrinsic markers of vascularization(1,7). In the case reported here, there wereno signs of increased perfusion.

The main differential diagnoses of LCH are forms of non-Langerhans histiocytosis(Rosai-Dorfman disease, Erdheim-Chester disease, and hemophagocytic syndrome),sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, meningioma, hemangiopericytoma, and solitary fibroustumor(1). Although there is nosubstantive consensus on the treatment of LCH, it is based on the location and number oflesions, the main therapeutic options being surgery and chemotherapy with variouscombinations of interferon, vinblastine, cladribine, and methotrexate.

Although uncommon, LCH should be considered in the differential diagnosis of extra-axialexpansile lesions in children. It should be considered especially for lesions presentingan intermediate to hypointense signal in T2-weighted MRI sequences.

REFERÊNCIAS1.Gabbay LB, Leite CC, Andriola RS, et al. Histiocytosis: a review focusing on neuroimagingfindings. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2014;72:548–558. doi: 10.1590/0004-282x20140063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]2.Grois N, Fahrner B, Arceci RJ, et al. Central nervous system disease in Langerhans cellhistiocytosis. J Pediatr. 2010;156:873–881. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]3.Pyun JM, Park H, Moon KC, et al. Late-onset Langerhans cell histiocytosis with cerebellar ataxiaas an initial symptom. Case Rep Neurol. 2016;8:218–223. doi: 10.1159/000450884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]4.Le Guennec L, Martin-Duverneuil N, Mokhtari K, et al. Neurohistiocytose langerhansienne. Presse Med. 2017;46:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2016.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]5.Haroche J, Cohen-Aubart F, Rollins BJ, et al. Histiocytoses: emerging neoplasia behindinflammation. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e113–e125. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]6.Miyake Y, Ito S, Tanaka M, et al. Spontaneous regression of infantile dural-based non-Langerhanscell histiocytosis after surgery: case report. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;15:372–379. doi: 10.3171/2014.10.PEDS14378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]7.Hingwala D, Neelima R, Kesavadas C, et al. Advanced MRI in Rosai-Dorfman disease: correlation withhistopathology. J Neuroradiol. 2011;38:113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]Articles from Radiologia Brasileira are provided here courtesy of Colegio Brasileiro De Radiologia